If you’ve ever watched a game and wondered, “How do brands actually measure how often their logo shows up on screen?” you’re already asking an ACR question. Similarly, insights like:

- How many minutes did Brand X’s logo appear on the jersey?

- Did that new sponsor actually get the exposure they paid for?

- Is my logo being used in places it shouldn’t be?

are all powered by Automatic Content Recognition (ACR) technology. It looks at raw audio/video and figures out what is in it without relying on filenames, tags, or human labels.

In this post, we’ll zoom into one very practical slice of ACR: Recognizing brand logos in images or video using a completely open-source stack.

Table of contents

- Introduction to Automatic Content Recognition

- Why Logo ACR Is a Big Deal?

- The Big Idea: From Pixels to Vectors to Matches

- Logo Dataset

- An Open-Source Stack for Logo ACR

- Euclidean Distance for Logo Matching

- Step-by-Step Model Pipeline (Logo ACR)

- Visualizing Similarity and Matching

- Accuracy and Threshold Tuning

- Conclusion

- Next Steps

Introduction to Automatic Content Recognition

Automatic Content Recognition (ACR) is a media recognition technology (similar to facial recognition technology) capable of recognizing the contents in media without human intervention. Whether you have witnessed an app on your Smartphone identifying the song that is being played, or a streaming platform labeling actors in a scene, you have been experiencing the work of ACR. Devices using ACR capture a “fingerprint” of audio or video and compare it to a database of content. When a match is found, the system returns metadata about that content, for example, the name of a song or the identity of an actor on screen but it can also be used to recognize logos and brand marks in images or video. This article will illustrate how to build an ACR system focused on recognizing logos in an image or video.

We will walk through a step-by-step logo recognition pipeline that assumes a metric-learning embedding model (e.g., a CNN/ViT trained with contrastive/triplet, or ArcFace-style loss) to produce ℓ2-normalized vectors for logo crops and use Euclidean distance (L2 norm) to match new images against a gallery of brand logos. The aim is to show how a gallery of logo exemplars (imaginary logos created for this article) can be used as our reference database and how we can automatically determine which logo appears in a new image by locating the nearest match in our embedding space.

Once the system is built, we will measure the system accuracy and comment on the process of selecting the appropriate distance threshold to be used in effective recognition. At the end of it, you will have an idea of the elements of a logo recognition ACR pipeline and be capable of testing your dataset of logo images or any other use case.

Why Logo ACR Is a Big Deal?

Logos are the visual shorthand for brands. If you can detect them reliably, you unlock a whole set of high-value use cases:

- Sponsorship & ad verification: Did the logo appear when and where the contract promised? How long was it visible? On which channels?

- Brand safety & compliance: Is your logo showing up next to content you don’t want to be associated with? Are competitors ambushing your campaign?

- Shoppable & interactive experiences: See a logo on screen → tap your phone or remote → see products, offers, or coupons in real time.

- Content search & discovery: “Show me all clips where Brand A, Brand B, and the new stadium sponsor appear together.”

At the core of all these scenarios is the same question:

Given a frame from a video, which logo(s) are in it, if any?

That’s exactly what we’ll design.

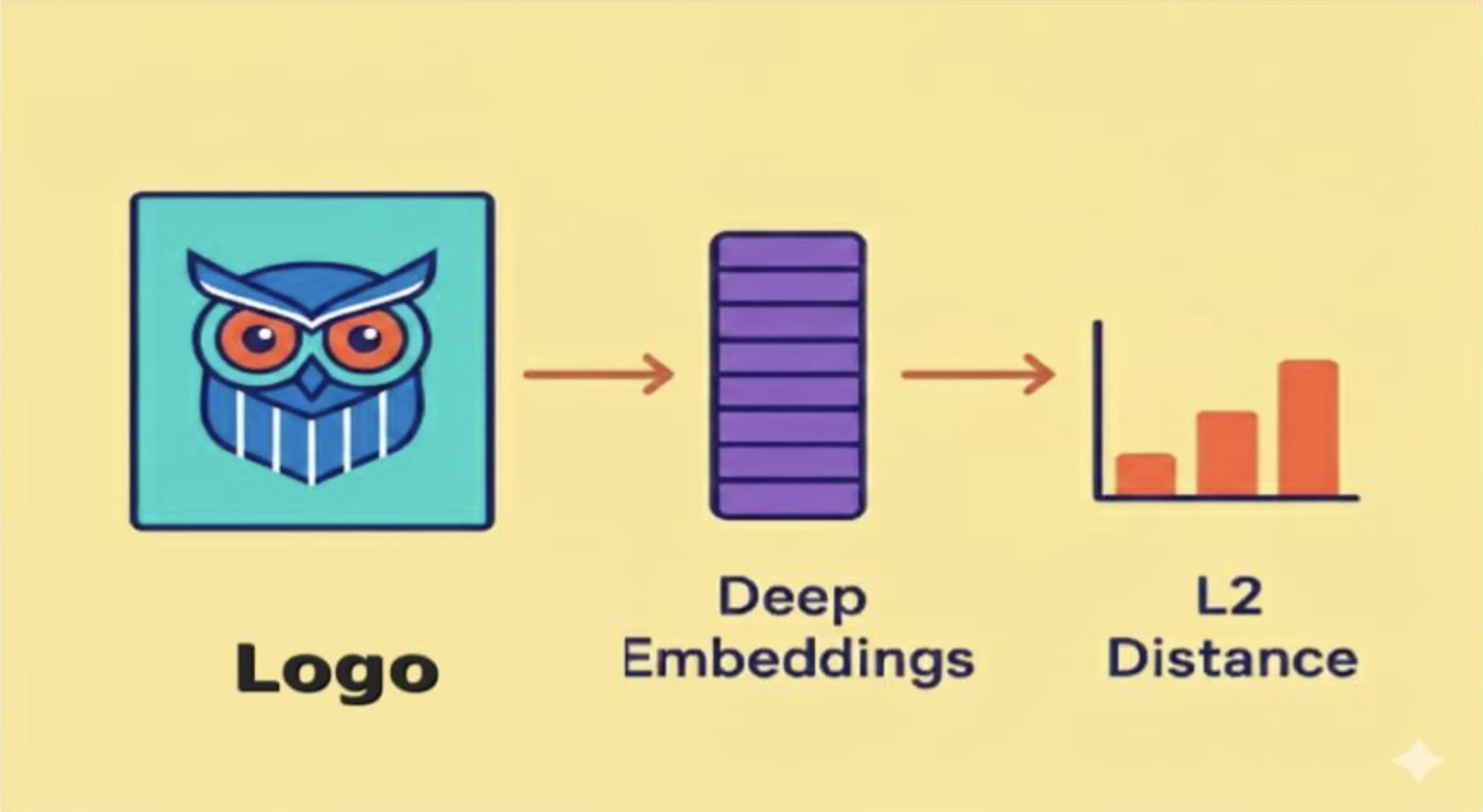

The Big Idea: From Pixels to Vectors to Matches

Modern ACR is basically a three-step magic trick:

- Look at the signal – Grab frames from the video stream.

- Turn images into vectors – Use a deep model to map each logo crop to a compact numerical vector (an embedding).

- Search in vector space – Compare that vector to a gallery of known logo vectors using a vector database or ANN library.

If a new logo crop lands close enough to a cluster of “Brand X” vectors, we call it a match. That’s it. Everything else, detectors, thresholds, and indexing, are just making this faster, more robust, and more scalable.

Logo Dataset

To build our Logo recognition ACR system, we need a reference dataset of Logos with known identities. We will use a collection of Log images created artificially using AI for this case study. Even though we are using some random imaginary logos for this article, this can be extended even to downloading known logos if you have the license to use them or an existing research dataset. In our case, we will work with a small sample: for example, a dozen brands with 5 to 10 images per brand.

The brand name of the logo is provided as a label of each logo in the dataset, and it is the ground-truth identity.

These logos show variability that matters for recognition, for example, in colorways (full-color, black/white, inverted), layout (horizontal vs. stacked), wordmark vs. icon-only, background/outline treatments, and, in the wild, they appear under different scales, rotations, blur, occlusions, lighting, and perspectives. The system should be based on the similarities in the logo, as it will appear very different in situations. We suppose that we have cropped logo images so that our recognition model actually takes as input only the logo region.

Representation in the ACR System

As an example, consider that we have in our database logos of known logos as Photo A, Photo B, Photo C, etc. (each of them is an imaginary logo generated using AI). Each of these logos will be represented as a numerical encoding in the ACR system and stored.

Below, we show an example of one imaginary brand logo in two different images from our dataset:

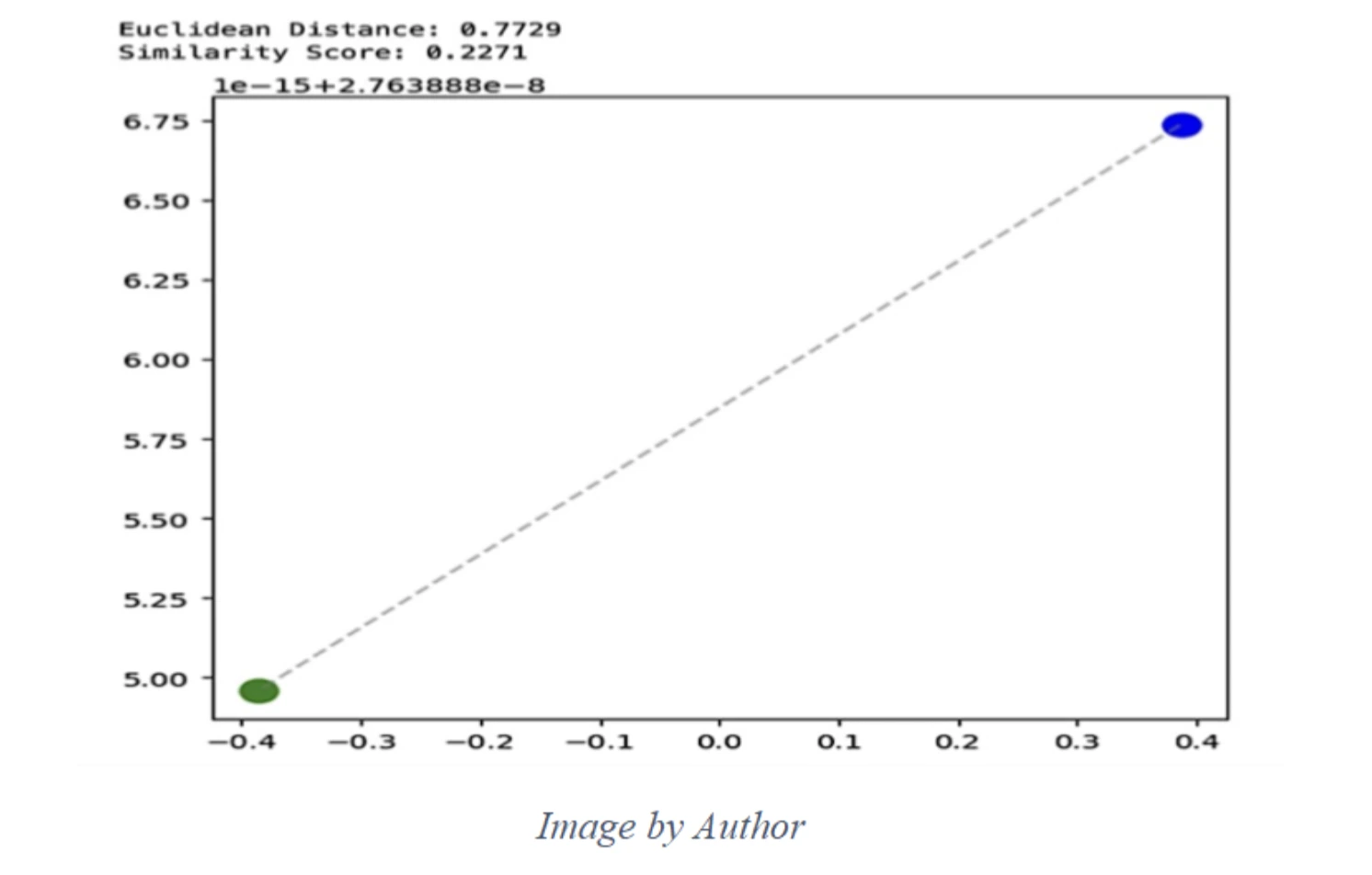

We will use a pre-trained model to detect the Logo in two images of the above same brand.

This figure is showing two points (green and blue), the straight-line (Euclidean) distance between them, and then a “similarity score” that’s just a simple transform of that distance.

An Open-Source Stack for Logo ACR

In practice, many teams today use lightweight detectors such as YOLOv8-Nano and backbones like EfficientNet or Vision Transformers, all available as open-source implementations.

Core components

- Deep learning framework: PyTorch or TensorFlow/Keras; used to train and run the logo embedding model.

- Logo detector: Any open-source object detector (YOLO-style, SSD, RetinaNet, etc.) trained to find “logo-like” regions in a frame.

- Embedding model: A CNN or Vision Transformer backbone (ResNet, EfficientNet, ViT, …) with a metric-learning head that outputs unit-normalized vectors.

- Vector search engine: FAISS library, or a vector DB like Milvus / Qdrant / Weaviate to store millions of embeddings and answer “nearest neighbor” queries quickly.

- Logo data: Synthetic or in-house logo images, plus any public datasets that explicitly allow your intended use.

You can swap any component as long as it plays the same role in the pipeline.

Step 1: Finding Logos in the Wild

Before we can recognize a logo, we have to find it.

1. Sample frames

Processing every single frame in a 60 FPS stream is overkill. Instead:

- Sample 2 to 4 frames per second per stream.

- Treat each sampled frame as a still image to inspect.

This is usually enough for brand/sponsor analytics without breaking the compute budget.

2. Run a logo detector

On each sampled frame:

- Resize and normalize the image (standard pre-processing).

- Feed it into your object detector.

- Get back bounding boxes for regions that look like logos.

Each detection is:

(x_min, y_min, x_max, y_max, confidence_score)

You crop those regions out; each crop is a “logo candidate.”

3. Stabilize over time

Real-world video is messy: blur, motion, partial occlusion, multiple overlays.

Two easy tricks help:

- Temporal smoothing – combine detections across a short window (e.g., 1–2 seconds). If a logo appears in 5 consecutive frames and disappears in one, don’t panic.

- Confidence thresholds – discard detections below a minimum confidence to avoid obvious noise.

After this step, you have a stream of reasonably clean logo crops.

Step 2: Logo Embeddings

Now that we can crop logos from frames, we need a way to compare them that’s smarter than raw pixels. That’s where embeddings come in.

An embedding is just a vector of numbers (for example, 256 or 512 values) that captures the “essence” of a logo. We train a deep neural network so that:

- Two images of the same logo map to vectors that are close together.

- Images of different logos map to vectors that are far apart.

A common way to train this is with a metric-learning loss such as ArcFace. You don’t need to remember the formula; the intuition is:

“Pull embeddings of the same brand together in the embedding space, and push embeddings of different brands apart.”

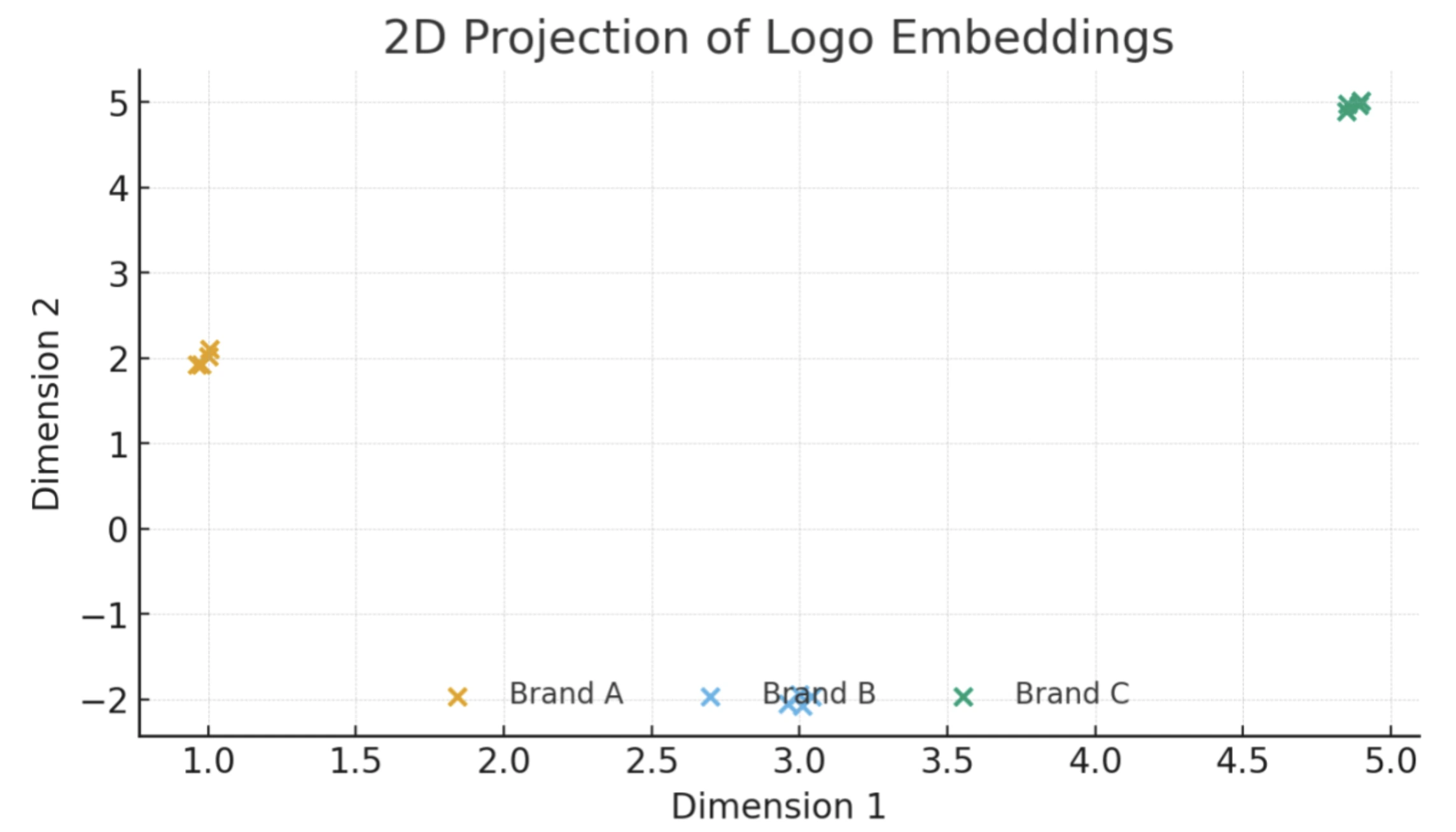

After training, the network behaves like a black box:

Below: Scatter plot showing a 2D projection of logo embeddings for three known brands/logos (A, B, C). Each point is one logo image, which is embedded from the same brand cluster tightly, showing clear separation between brands in the embedding space.

We can use a logo embedding model trained with the ArcFace-style (additive angular margin) loss to produce ℓ2-normalized 512-D vectors for each logo crop. There are many open-source ways to build a logo embedder. The simplest way is to load a general vision backbone (e.g., ResNet/EfficientNet/ViT) with an ArcFace-style (additive angular margin) head.

Let’s look at how this works in code-like form. We’ll assume:

- embedding_model(image) takes a logo crop and returns a unit-normalized embedding vector.

- detect_logos(frame) returns a list of logo crops for each frame.

- l2_distance(a, b) computes the Euclidean distance between two embeddings.

First, we build a small embedding database for our known brands:

embedding_model = load_embedding_model("arcface_logo_model.pt") # PyTorch / TF model

brand_db = {} # dict: brand_name -> list of embedding vectors

for brand_name in brands_list:

examples = []

for img_path in logo_images[brand_name]: # paths to example images for this brand

img = load_image(img_path)

crop = preprocess(img) # resize / normalize

emb = embedding_model(crop) # unit-normalized logo embedding

examples.append(emb)

brand_db[brand_name] = examplesAt runtime, we recognize logos in a new frame like this:

def recognize_logos_in_frame(frame, threshold):

crops = detect_logos(frame) # logo detector returns candidate crops

results = []

for crop in crops:

query_emb = embedding_model(crop)

best_brand = None

best_dist = float("inf")

# find the closest brand in the database

for brand_name, emb_list in brand_db.items():

# distance to the closest example for this brand

dist_to_brand = min(l2_distance(query_emb, e) for e in emb_list)

if dist_to_brand < best_dist:

best_dist = dist_to_brand

best_brand = brand_name

if best_dist < threshold:

results.append({

"brand": best_brand,

"distance": best_dist,

# you would also include bounding box from the detector

})

else:

results.append({

"brand": None, # unknown / not in catalog

"distance": best_dist,

})

return resultsIn a real system, you wouldn’t loop over every embedding in Python. You’d drop the same idea into a vector index such as FAISS, Milvus, or Qdrant, which are open-source engines designed to handle nearest-neighbor search over millions of embeddings efficiently. But the core logic is exactly what this pseudocode shows:

- Embed the query logo,

- Find the closest known logo in the database,

- Check if the distance is below a threshold to decide if it’s a match.

Euclidean Distance for Logo Matching

We can now express logos as numerical vectors, but how do we compare them? Embeddings have a few common similarity measures, and Euclidean distance and cosine similarity are the most used. Because our logo embeddings are ℓ2-normalized (ArcFace-style), cosine similarity and Euclidean distance give the same ranking (one can be derived from the other). Our distance measure will be Euclidean distance (L2 norm).

Euclidean distance between two feature vectors (x) and (y) (each of length (d), here (d = 512)) is defined as: distance=√(Σ(xi−yi)²)

After the square root, this is the straight-line distance between the two points in 512-D space. A smaller distance means the points are closer, which—by how we trained the model—indicates the logos are more likely to be the same brand. If the distance is large, they are different brands. Using Euclidean distance on the embeddings turns matching into a nearest-neighbor search in feature space. It’s effectively a K-Nearest Neighbors approach with K=1 (find the single closest match) plus a threshold to decide if that match is confident enough.

Nearest-Neighbor Matching

Using Euclidean distance as our similarity measure is straightforward to implement. We calculate the distance between a query logo’s embedding and each stored brand embedding in our database, then take the minimum. The brand corresponding to that minimum distance is our best match. This method finds the nearest neighbor in embedding space—if that nearest neighbor is still fairly far (distance larger than a threshold), we conclude the query logo is “unknown” (i.e., not one of our known brands). The threshold is important to avoid false positives and should be tuned on validation data.

To summarize, Euclidean distance in our context means: the closer (in Euclidean distance) a query embedding is to a stored embedding, the more similar the logos, and hence the more likely the same brand. We will use this principle for matching.

Step-by-Step Model Pipeline (Logo ACR)

Let’s break down the entire pipeline of our logo detection ACR system into clear steps:

1. Data Preparation

Collect images of known brands’ logos (official artwork + “in-the-wild” shots). Organize by brand (folder per brand or (brand, image_path) list). For in-scene images, run a logo detector to crop each logo region; apply light normalization (resize, padding/letterbox, optional contrast/perspective fix).

2. Embedding Database Creation

Use a logo embedder (ArcFace-style/additive-angular-margin head on a vision backbone) to compute a 256–512D vector for every logo crop. Store as a mapping brand → [embeddings] (e.g., a Python dict or a vector index with metadata).

3. Normalization

Ensure all embeddings are ℓ2-normalized (unit length). Many models output unit vectors; if not, normalize so distance comparisons are consistent.

4. New Image / Stream Query

For each incoming image/frame, run the logo detector to get candidate boxes. For each box, crop and preprocess exactly as in training, then compute the logo embedding.

5. Distance Calculation

Compare the query embedding to the stored catalog using Euclidean (L2) or cosine (equivalent for unit vectors). For large catalogs or real-time streams, use an ANN index (e.g., FAISS HNSW/IVF) instead of brute force.

6. Find Nearest Match

Take the nearest neighbor in embedding space. If you keep multiple exemplars per brand, use the best score per brand (max cosine / min L2) and pick the top brand.

7. Threshold Check (Open-set)

Compare the best score to a tuned threshold.

- Score passes → recognize the logo as that brand.

- Score fails → unknown (not in catalog). Thresholds are calibrated on validation pairs to balance false positives vs. misses; optionally apply temporal smoothing across frames.

8. Output Result

Return brand id, bounding box, and similarity/distance. If unknown, handle per policy (e.g., “No match in catalog” or route for review). Optionally log matches for auditing and model improvement.

Visualizing Similarity and Matching

The similarity scores (or distances) are often handy to visualize the way the system is making decisions. As an example, provided with a query image, we can examine the calculated distance to every candidate in the database. Ideally, the right identity will be far less than others and will establish a distinct separation between the closest one and the rest.

The chart below illustrates an example. We had a query image of Logo C, and we computed its Euclidean distance to the embeddings of five candidate Logos (LogoA through LogoE) in our database. We then plotted those distances:

In this example, the clear separation between the genuine match (LogoC) and the others makes it easy to choose a threshold. In practice, distances will vary depending on the pair of images. Two Logos of the same brand might sometimes yield a distance slightly higher, especially if the Logos are very different, and two different brand Logos can occasionally have a surprisingly low distance if they look alike. That’s why threshold tuning is needed using a validation set.

Accuracy and Threshold Tuning

To measure system accuracy, we may run the system on a test set of logo images (where there is known identity, but not in the database) and count the number of times the system identifies the brands correctly. We would vary the distance threshold and observe the trade-off between false positives, or the detection of a known logo of a brand as another one, and false negatives, or the failure to detect a known logo because the distance is larger than the threshold. In order to pick a good value, a plot of the ROC curve or simply a calculation of precision/recall at different thresholds can be relevant.

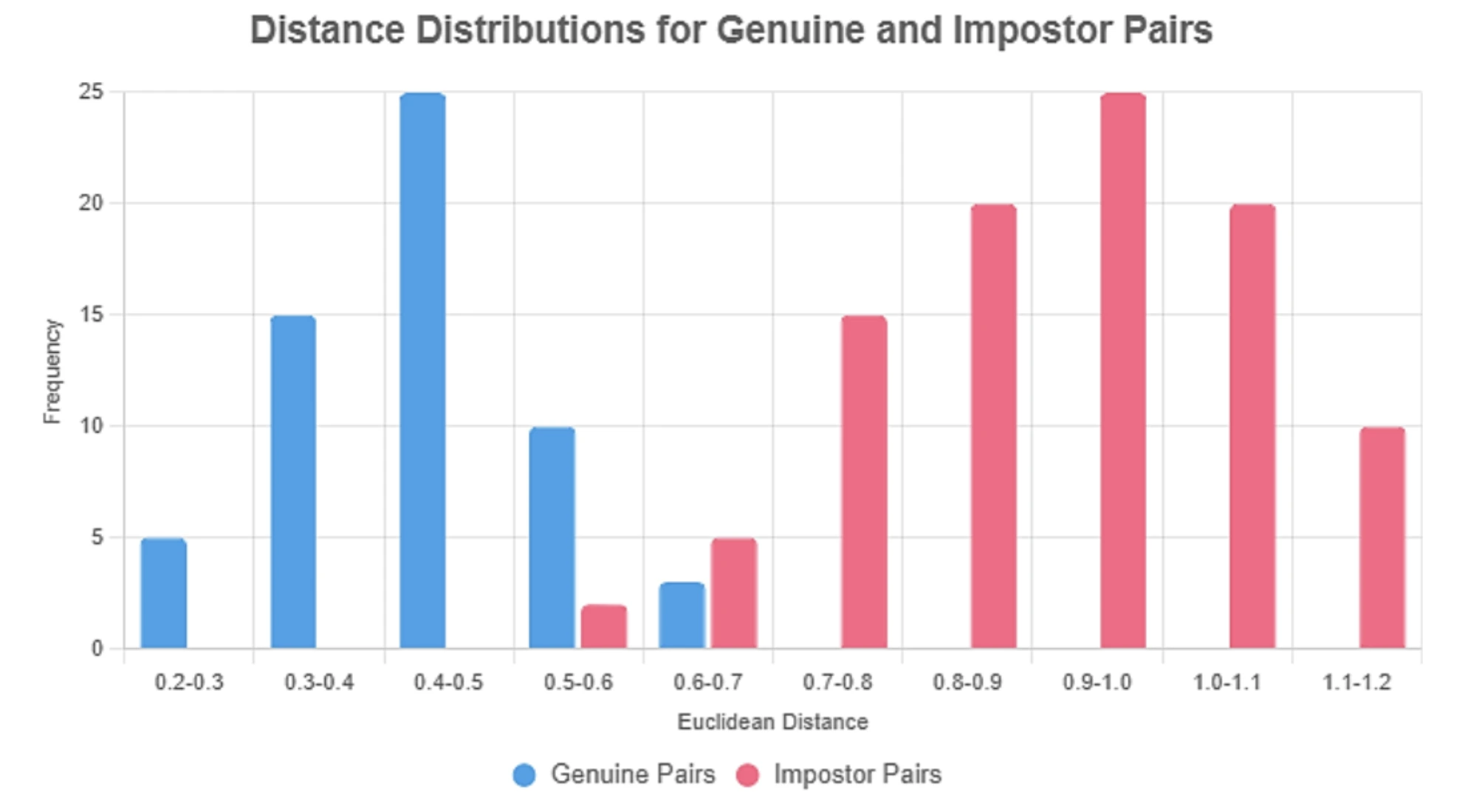

How to tune the threshold (simple, repeatable):

- Build pairs.

– Genuine pairs: embeddings from the same brand (different files/angles/colors).

– Impostor pairs: embeddings from different brands (include look-alike marks, color-inverted versions). - Score pairs. Compute Euclidean (L2) or cosine (on unit vectors, they rank identically).

- Plot histograms. You should see two distributions: same-brand distances clustered low and different-brand distances higher.

- Choose a threshold. Pick the value that best separates the two distributions for your target risk (e.g., the distance where FAR = 1%, or the argmax of F1).

- Open set check. Add non-logo crops and unknown brands to your negatives; verify the threshold still controls false accepts

Below: Histogram of Euclidean distances for same-brand (genuine) vs different-brand (impostor) logo pairs. The dashed line shows the selected threshold separating most genuine from impostor matches.

In summary, to achieve good accuracy:

- Use multiple logos per brand if possible, when building the database, or use augmentation, so the model has a better chance of getting a representative embedding

- Evaluate distances on known validation pairs to understand the range of same-brand vs different-brand distances.

- Set the threshold to balance missed recognitions vs false alarms based on those distributions. You can start with commonly used values (like 0.6 for 128-D embeddings or around 1.24 for 512-D threshold), then adjust.

- Fine-tune as needed: If the system is making mistakes, analyze them. Are the false positives coming from specific look-alike logos? Are the false negatives coming from low-quality images? This analysis can guide adjustments (maybe a lower threshold, or adding more reference images for certain logos, etc.).

Conclusion

In this article, we built a simplified Automatic Content Recognition system for identifying brand logos in images using deep logo embeddings and Euclidean distance. We introduced ACR and its use cases, assembled an open-licensed logo dataset, and used an ArcFace-style embedding model (for logos) to convert cropped logos into a numerical representation. By comparing these embeddings with a Euclidean distance measure, the system can automatically recognize a new logo by finding the nearest match in a database of known brands. We demonstrated how the pipeline works with code snippets and visualized how a decision threshold can be applied to improve accuracy.

Results: With a well-trained logo embedding model, even a simple nearest-neighbor approach can achieve high accuracy. The system correctly identifies known brands in query images when their embeddings fall within a suitable distance threshold of the stored templates. We emphasized the importance of threshold tuning to balance precision and recall, a critical step in real-world deployments.

Next Steps

There are several ways to extend or improve this ACR system:

- Scaling Up: To support thousands of brands or real-time streams, replace brute-force distance checks with an efficient similarity index (e.g., FAISS or other approximate nearest neighbor methods)

- Detection & Alignment: Perform logo detection with a fast detector (e.g., YOLOv8-Nano/EfficientDet-Lite/SSD) and apply light normalization (resize, padding, optional perspective/contrast fixes) so the embedder sees consistent crops.

- Improving Accuracy: Fine-tune the embedder on your logo set and add harder augmentations (rotation, scale, occlusion, color inversion). Keep multiple exemplars per brand (color/mono/legacy marks) or use prototype averaging..

- ACR Beyond Logos: The same embedding + nearest-neighbor approach extends to product packaging, ad-creative matching, icons, and scene text snippets.

- Legal & Ethics: Respect trademark/IP, dataset licenses, and image rights. Use only assets with permission for your purpose (including commercial use). If images include people, comply with privacy/biometric laws; monitor regional/brand coverage to reduce bias.

Automatic Content Recognition is a powerful deep learning technology that powers many of the devices and services we use every day. By understanding and building a simple system for detection & recognition with Euclidean distance, we gain insight into how machines can “see” and identify content. From indexing logos or videos to enhancing viewer experiences, the possibilities of ACR are vast, and the approach outlined here is a foundation that can be adapted to many exciting applications.