I have spent the last several years watching enterprise collaboration tools get smarter. Join a video call today, and there’s a good chance five or six AI agents are running simultaneously: transcription, speaker identification, captions, summarization, task extraction. On the product side of it, each agent gets evaluated in isolation. Separate dashboards, separate metrics. Transcription accuracy? Check. Response latency? Check. Error rates? All green.

But here is what I consistently observe as a UX Researcher: users are frustrated, adoption stalls, and teams are trying to identify the root cause. Per the metrics, the dashboards look fine. Every individual component passes its tests. So, where are users truly struggling?

The answer, almost every time, is orchestration. The agents work fine alone. They fall apart together. And the only way I have found to catch these failures is through user experience research methods that engineering dashboards were never designed to capture.

Table of contents

The Orchestration Visibility Gap

Here’s an example of gaps that need a deeper understanding through user research: a transcription agent reports 94% accuracy and 200-millisecond response times. But what the dashboard does not show is that users are abandoning the feature because two agents gave them conflicting information about who said what in a meeting. The transcription agent and the speaker identification agent disagreed, and the user lost trust in the whole system.

This problem is about to get much bigger. Right now, fewer than 5% of enterprise apps have task-specific AI agents built in. Gartner thinks that’ll jump to 40% by the end of 2026. We are headed toward a world where multiple agents coordinate on almost everything. If we cannot figure out how to evaluate orchestration quality now, we will be scaling broken experiences.

UX Research Methods Adapted for Agent Evaluation

Standard UX methods need some tweaking when you are dealing with AI that behaves differently each time. I have landed on three approaches that actually work for catching orchestration problems.

1. Think-Aloud Protocols for Agent Handoffs

In traditional think-aloud studies, you ask people to narrate what they are doing. For AI orchestration, I layer in what I call system attribution probes at key handoff points. I pause and ask participants to describe what they believe just happened behind the scenes, then map their responses against the actual agent architecture. Most users are unaware that separate agents handle transcription, summarization, and task extraction. When something goes wrong: a transcription error, for instance, they blame “the AI” as a monolith, even when the summarization and routing worked perfectly. User feedback alone won’t get you there. What I’ve found works is mapping what people think the system just did against what actually happened. Where those two diverge, that’s where orchestration is failing. That’s where the design work needs to happen

2. Journey Mapping Across Agent Touchpoints

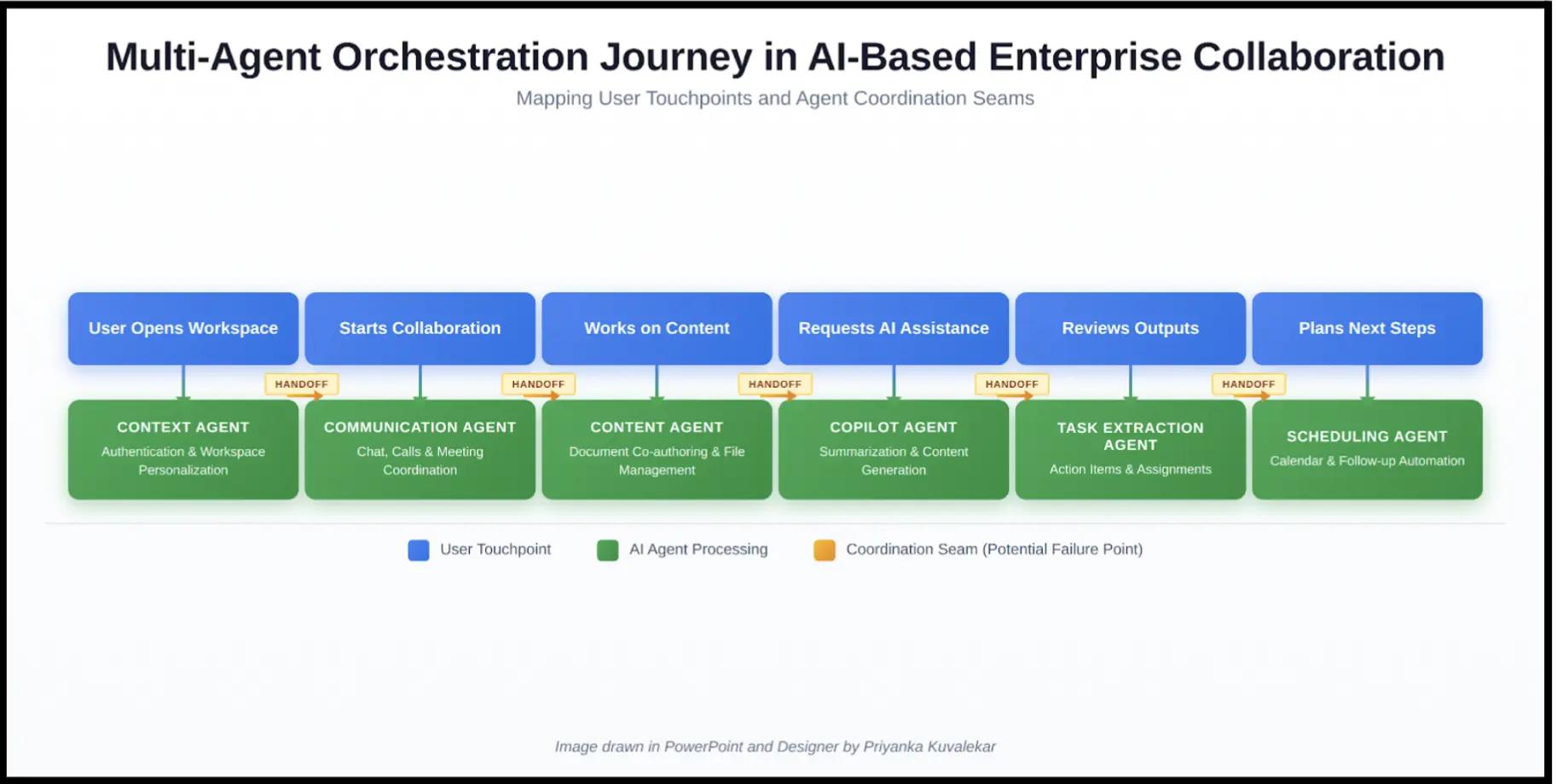

Consider a single video call. The user clicks to join, and a calendar agent handles authentication. A speech-to-text agent transcribes, a display agent renders captions, and when the call ends, a summarization agent writes up the meeting while a task extraction agent pulls out action items. A scheduling agent might then book follow-ups. That’s six agents in one workflow and six potential failure points.

I build dual-layer journey maps: the user’s experience on top, the responsible agent underneath. When those layers fall out of sync – when users expect continuity but the system has handed off to a new agent; that’s where confusion sets in, and where I focus my research to unpack deeper issues.

3. Heuristic Evaluation for Agent Transparency

Nielsen Norman’s classic heuristics remain foundational, but multi-agent systems require us to extend them. “Visibility of system status” has a different meaning when six agents are working simultaneously; not because users need to understand the underlying architecture, but because they need enough clarity to recover when something goes wrong. The goal isn’t architectural transparency; it’s actionable transparency. Can users tell what the system just did? Can they correct or undo it? Do they know where the system’s limitations are? These criteria reframe orchestration as a UX problem, not just an infrastructure concern.

I’ve run heuristic evaluations where the interface was polished and interaction patterns felt familiar, yet users still struggled. The surface design passed every traditional check, but when the system failed, users had no way to diagnose what went wrong or how to fix it. They didn’t need to know which agent caused the issue. They needed a clear path to recovery.

Case Study: Enterprise Calling AI

Here’s a real situation I worked on that illustrates why orchestration quality can matter as much as individual agent performance.

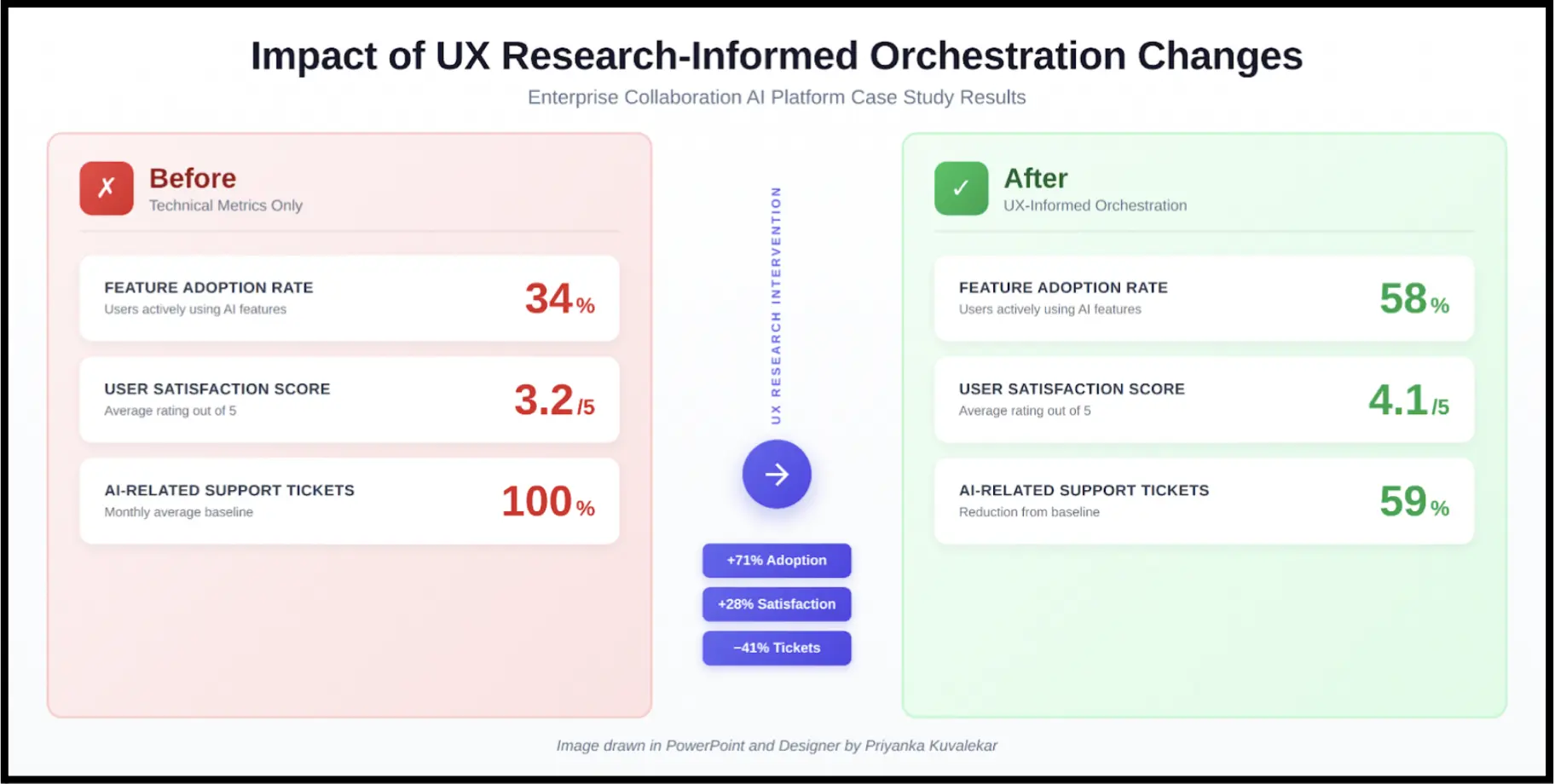

An enterprise calling platform had deployed AI for transcription, speaker identification, translation, summarization, and task extraction. Every component hit its performance targets. Transcription accuracy was above 95%. Speaker identification ran at 89% precision. Task extraction caught action items in 78% of meetings. However, user satisfaction was at 3.2 out of 5, and only 34% of eligible users had adopted the AI features. The product team’s instinct was to improve the models. I suspected the problem was in how the agents worked together.

We ran think-aloud sessions and discovered something the dashboards never showed: users assumed that edits they made to live captions would carry over to the final transcript. They didn’t. The systems were completely separate. When I built out the journey map, plotting user actions on one layer and agent responsibility on another, I noticed the timing misalignment immediately. Action items were arriving in users’ task lists before the meeting summary was even ready. On the user layer, this looked like tasks appearing out of nowhere. On the agent layer, it was simply the task extraction agent finishing before the summarization agent. Both were performing correctly in isolation. The orchestration made them feel broken.

Heuristic evaluation surfaced a subtler issue: when the translation and transcription agents disagreed about speaker identity, the system silently picked one. No indication, no confidence signal, no way for users to intervene.

This pointed us toward a design hypothesis: the problem wasn’t agent accuracy, it was coordination and recoverability. Rather than lobby for model improvements, we focused on three orchestration-level changes. First, we synchronized timing so summaries and tasks arrived together, restoring context. Second, we built unified feedback mechanisms that let users correct outputs once rather than per-agent. Third, we added status indicators showing when handoffs were occurring.

Three months later, adoption had jumped from 34% to 58%. Satisfaction scores significantly improved with ratings of 4.1 out of 5. Support tickets about AI features dropped by 41%. We hadn’t improved a single model. The engineering team didn’t think UX changes alone could move those numbers. Fair enough, honestly. But three months of data made it hard to argue. Agent coordination isn’t just an infrastructure problem. It’s a UX problem, and it deserves that level of attention.

A Three-Layer Evaluation Framework

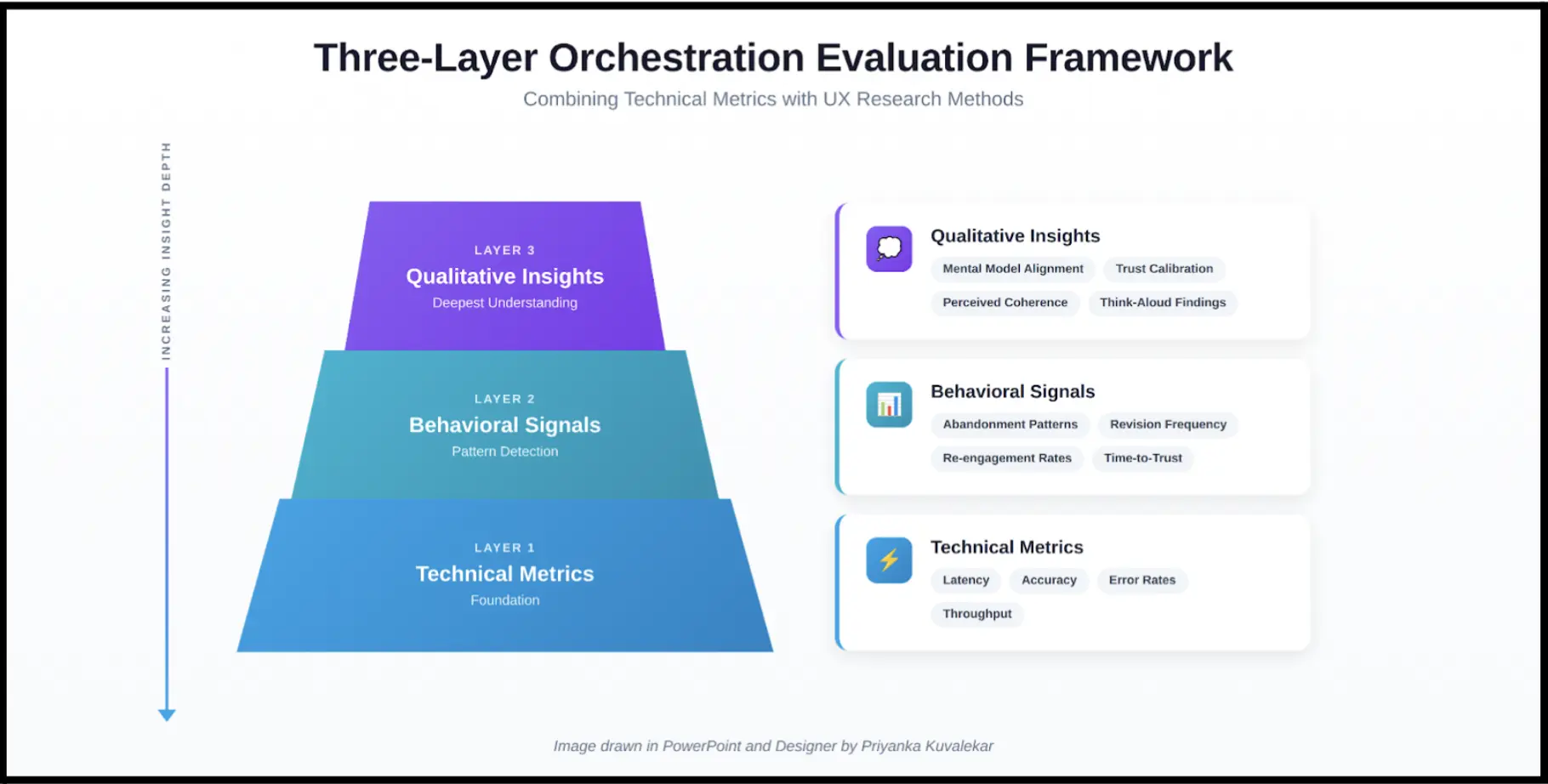

Based on what I have seen across multiple deployments, I now recommend evaluating orchestration on three levels. Layer one is technical metrics: latency, accuracy, and error rates for each agent. You still need these. They catch component-level failures. But they cannot see coordination problems.

Layer two is behavioral signals. Track where users abandon workflows, how often they revise AI-generated outputs, and whether they come back after their first experience. These patterns hint at orchestration issues without requiring direct user feedback.

Layer three is qualitative research. Do users understand what the agents are doing and why are they doing it? Do they trust the outputs? Does the whole system feel coherent and accessible or disjointed? McKinsey’s 2025 AI survey found that 88% of organizations use AI somewhere, but most have not moved past pilots with limited business impact (McKinsey, 2025). I suspect a big part of that gap comes from orchestration quality that nobody is measuring properly.

What This Means for Product Teams

In most organizations I have worked with, UX researchers and AI engineers have limited collaboration. Engineers tune individual agents against benchmarks. UX researchers test interfaces. Nobody owns the space between agents where coordination happens. That gap is exactly where these failures live.

Deloitte estimates that a quarter of companies using generative AI will launch agentic pilots this year, with that number doubling by 2027 (Deloitte, 2025). Teams that implement orchestration evaluation early will have a real advantage. Teams that do not will keep wondering why their AI features are not landing with users. The investment required is not massive. It includes UX researchers in orchestration design discussions, building telemetry that captures agent transitions, and running regular studies focused specifically on multi-agent workflows.

Conclusion

As AI products evolve from single assistants to coordinated agent systems, the definition of “working” has to evolve with them. A set of agents that each pass their individual benchmarks can still deliver a broken user experience. Performance dashboards won’t catch it because they’re measuring the wrong layer. User complaints won’t clarify it because people blame “the AI” without knowing which component failed or why.

This is exactly where UX research earns its seat at the table. Not as a final check before launch, but as a discipline woven throughout the product lifecycle. UXR helps teams answer the earliest questions: Are we solving the right problem? Who are we solving it for? It shapes success metrics that reflect real user outcomes, not just model performance. It evaluates how agents behave together, not just in isolation.

UX research shows you what earns trust and what chips away at it. It makes sure accessibility gets built in from the start, not bolted on later when the system is too tangled to fix properly. None of this is separate work. It’s all connected, each layer feeding into the next. And as AI systems get more autonomous, more opaque, this kind of rigor isn’t optional. The problem is, when teams are moving fast, research feels like a speed bump. Something to circle back to after launch.

But the cost of skipping it compounds quickly. The orchestration problems I’ve described don’t surface in QA. They surface when real users encounter real complexity, and by then, trust is already damaged.

AI systems are only getting more complex, more autonomous, and more embedded in how people work. UX research is how we keep those systems accountable to the people they’re meant to serve.

Frequently Asked Questions

This is one of the most common frustrations I see in enterprise AI. Individual agents pass their benchmarks in isolation, but the real problems show up when multiple agents have to work together. Orchestration failures happen at the handoffs, like when a transcription agent and speaker identification agent disagree about who said what, or when task extraction finishes before summarization, and users receive action items with no context.

These coordination issues never appear on component-level dashboards because each agent is technically doing its job. That’s precisely why user research methods are essential. They surface where the experience actually breaks down in ways that engineering metrics weren’t designed to catch.

Familiar methods like think-aloud protocols and journey mapping still work, but they need some adjustments for AI systems. In think-aloud studies, I’ve found it valuable to include what I call system attribution probes, moments where you pause and ask users to describe what they believe just happened behind the scenes. Journey maps benefit from a dual-layer approach: the user experience on top and the responsible agent underneath.

Orchestration problems lie where these layers are out of sync, and research should focus on identifying and evaluating these issues.

Longitudinal and ethnographic research are crucial to understand AI agent performance over time. Methods like diary studies and ethnography enable researchers to evaluate how users interact with the AI and shift their usage patterns across days or weeks, how that impacts trust, and identify new issues that may emerge.

Initial impressions of an AI system often differ from a user’s experience after continuous usage. Longitudinal studies reveal behaviors and workarounds that users develop, and touchpoints that contribute to users abandoning the feature entirely.

Based on what I’ve observed across multiple deployments, I recommend evaluating orchestration on three levels. Layer one covers the technical metrics such as latency, accuracy, and error rates for each agent.

Layer two focuses on behavioral signals such as workflow abandonment rates, how often users revise AI-generated outputs, and if they are returning users. These patterns hint at orchestration issues without requiring direct user feedback.

Layer three is qualitative research that evaluates if users actually trust the outputs, understand what the agents are doing, and perceive the system as coherent rather than disjointed. All three layers working together reveal problems that any single layer would miss.

Actionable transparency is not about teaching users the underlying architecture of every agent. Users need clarity and the ability to understand what the system just did, correct or recover from errors when something looks incorrect, and understand where the system’s limitations are.

Actionable transparency gives users clear paths to recover from errors.

When errors occur, users need to be informed about what their options are for resolving the issue and how to move forward. In practice, this could be unified feedback mechanisms to let users correct outputs once, rather than separately for each agent. It could also be status indicators that surface when handoffs are occurring, or undo functionality that works across the entire system. The goal is to design for recoverability. When orchestration breaks down, users can regain control and trust.

The most important shift is recognizing that the space between agents, where coordination happens, needs an owner. In most organizations I’ve worked with, engineers tune individual agents against benchmarks while UX researchers test interfaces. Nobody owns that gap, and that’s exactly where orchestration failures tend to live.

To close this gap, teams should bring UX researchers into orchestration design discussions early, not just at the end for interface testing. They should build telemetry that captures agent transitions and handoff points, not just individual agent performance. They should run regular studies focused specifically on multi-agent workflows rather than treating AI as a single monolithic feature. This does require intentional cross-functional collaboration to build better AI-products.