We have all enjoyed comics at some point, be it superhero comic books, comics in newspapers, or manga from Japan. Comics are brief, expressive, and encapsulate storytelling within just a few frames. But what if there is a new twist: what if you could use a comic generator to turn a short video clip into a comic strip of 4 panels with speech bubbles, expressive caricatures, and humour?

This is the idea behind Comic Generator or Comic War, not just another content generator. Still, a system I designed that takes a video clip and a short, brief creative idea and turns it into a finished comic strip image. It’s best to think of it as an imaginative partnership between two minds: one “writing the screenplay” and the other “drawing the comic.”

In this article, I will guide you through the journey of Comic War, explaining how it works, what components are required, which programming language to use for coding, the challenges I encountered during the process, and where the project can go from here.

Table of contents

The Concept of Comic War

All creative applications hinge on a standard formula:

- Input: What the user supplies.

- Transformation: How the system operates and furthers it.

- Output: The distillation of the experience that feels complete and polished.

For Comic War, the formula looks like:

- Input:

- A short video (like a YouTube short).

- A one-line creative idea (“Replace the fighting in the clip with exams”).

- Transformation:

- Systemically, the system analyzes the video, rewrites the idea into a full comic screenplay, and strictly enforces rules (layouts, style, humor).

- Output:

- A 4-panel comic strip in PNG format with dialogue balloons and captions.

What makes this fun? Because it’s personalized. Instead of random comics, you will receive a reinterpretation of the very clip you just selected, tailored around your one-line idea.

Consider a fight scene in a movie, echoing a student morphed into a goofy classroom battle about homework. This concoction of relatable visuals – familiar usernames with a surprising, personalised comic rewrite twist – is what makes Comic War addictive.

How Comic War Works

The pipeline is deconstructed as follows:

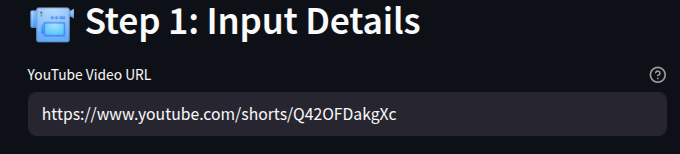

1. Inputs from the User

The process begins with two simple inputs:

- Video URL: Your source material (ideally YouTube shorts of around 30-40 secs).

- Idea Text: Your twist or theme.

Example:

Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/xQPAegqvFVs

Idea: Instead of violence, replace it with exams, like Yash saying

“Violence, violence, I don’t like violence, I avoid… but violence likes me.”

This is all the user has to provide, no complex settings, no sliders.

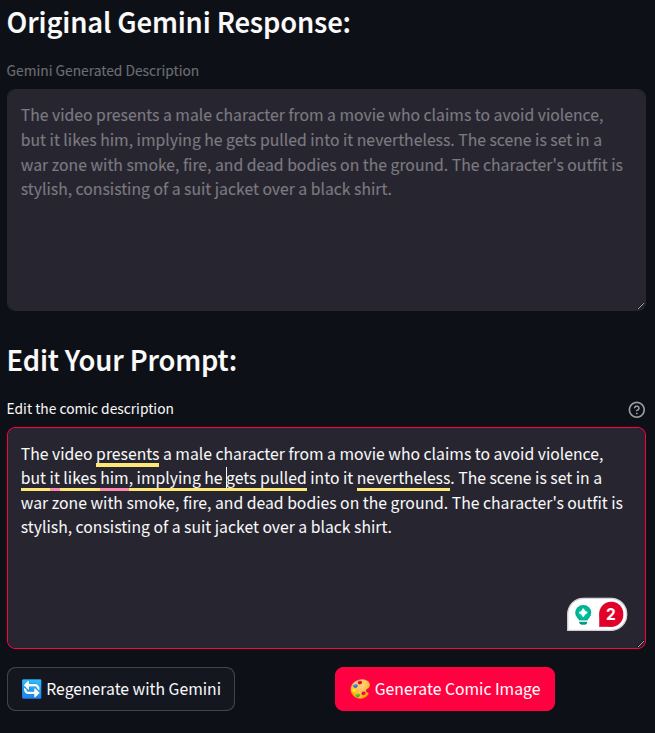

2. The Storyteller’s Job (Gemini)

The first part of the pipeline is what I refer to as the Storyteller. This is where the raw input of a YouTube video link and a brief idea you typed in gets transformed into something structured and usable.

When you paste a video URL, Gemini looks at the clip and extracts details:

- What’s happening in the scene?

- The mood (tense, dramatic, lighthearted).

- How the characters are moving and interacting.

Then it takes your one-liner (for example, “replace violence with exams”) and expands it into a comic script.

Now, this script isn’t just random text. It’s a screenplay for four panels that follows a strict set of rules. These rules were explicitly written into the system prompt that guides Gemini. They include:

- Always a 2×2 grid (so every comic looks consistent).

- Strictly a comic book style (no realistic rendering of characters).

- Dialogue written as meme-like speech bubbles.

- Captions added for extra punchlines or context.

- Nothing cropped, no cut-off text, and no risky references to copyrighted names.

By baking these constraints into the system prompt, I made sure the Storyteller always produces a clean, reliable screenplay. So instead of asking the image generator to “just make a comic,” Gemini prepares a fully structured plan that the next step can follow without guesswork.

3. The Illustrator’s Job (OpenAI / Imagen)

Once the script is ready, it’s passed on to the Illustrator.

This part doesn’t have to interpret anything; its single responsibility is to draw exactly what the Storyteller described.

The Illustrator function is addressed by an image generation model. In my setup, I have OpenAI’s GPT-Image-1 as my first choice, and Google’s Imagen as a secondary fallback if the first tool fails.

Here is what it looks like in practice:

- The Illustrator receives the screenplay as one long, detailed prompt.

- It then renders each panel with the characters, poses, background, and speech bubbles exactly as laid out.

- If OpenAI is unavailable, the same prompt gets sent to Imagen automatically, so you always get a finished comic.

This separation is the key to making Comic War reliable.

- Gemini thinks like a director: it writes the script and sets the stage.

- GPT-Image-1 or Imagen, they draw like artists, they follow the instructions without trying to change anything.

That’s why the output doesn’t feel messy or random. Each comic comes out as a proper four-panel strip, styled like a meme, and matches your idea almost one-to-one

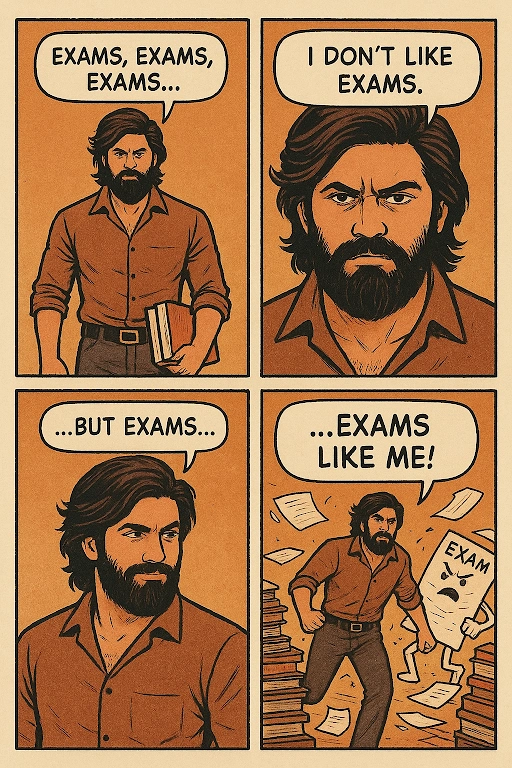

4. Output: The Final Comic

The result is a 4-panel comic strip image:

- Panels are clearly framed.

- Characters in the right poses.

- Speech bubbles with the right text.

- Humour intact.

And best of all, it feels like a finished comic you could be published online.

Technologies Behind Comic War

Here’s what powers the system:

- Language & Utilities

- Python is the glue language.

- dotenv for API key management.

- Pillow for image handling.

- base64 for processing image data.

- The Storyteller (Analysis + Prompting)

- Gemini (multimodal model): reads video + expands user input.

- The Illustrator (Image Generation)

- OpenAI GPT-Image-1 (a DALL·E variant).

- Fallback: Google Imagen (for resilience).

This dual approach ensures both creativity (from the storyteller) and visual consistency (from the illustrator).

Implementation

Now, let’s look into the actual implementation.

1. Configuration

@dataclass

class ComicGenerationConfig:

primary_service: str = "openai"

fallback_service: str = "imagen"

output_filename: str = "images/generated_comic.png"

openai_model: str = "gpt-image-1"

imagen_model: str = "imagen-4.0-generate-preview-06-06"

gemini_model: str = "gemini-2.0-flash"Where the models have been used in the following manner:

- OpenAI is the default illustrator.

- Imagen is the backup.

- Gemini is the storyteller.

2. Building the Screenplay

def extract_comic_prompt_and_enhance(video_url, user_input):

response = gemini_client.models.generate_content(

model="gemini-2.0-flash",

contents=[

Part(text=enhancement_prompt),

Part(file_data={"file_uri": video_url, "mime_type": "video/mp4"})

]

)

return response.textThis step rewrites a vague input into a detailed comic prompt.

3. Generating the Image

OpenAI (primary):

result = openai_client.images.generate(

model="gpt-image-1",

prompt=enhanced_prompt,

)

image_bytes = base64.b64decode(result.data[0].b64_json)Imagen (fallback):

response = gemini_client.models.generate_images(

model="imagen-4.0-generate-preview-06-06",

prompt=enhanced_prompt,

)

image_data = response.generated_images[0].imageFallback ensures reliability; if one illustrator fails, the other takes over.

4. Saving the Comic

def save_image(image_data, filename="generated_comic.png"):

img = PILImage.open(BytesIO(image_data))

img.save(filename)

return filenameThis method writes the comic strip to disk in PNG format.

5. Orchestration

def generate_comic(video_url, user_input):

enhanced_prompt = extract_comic_prompt_and_enhance(video_url, user_input)

image_data = generate_image_with_fallback(enhanced_prompt)

return save_image(image_data)All the steps tie together here:

- Extract screenplay to Generate comic to Save output.

Demo Example

Let’s see this in action.

Input:

- Video: Action short.

- Idea: “Replace violence with exams.”

Generated screenplay:

- Panel 1: Hero slumped at a desk: “Exams, exams, exams…”

- Panel 2: Slams book shut: “I don’t like exams!”

- Panel 3: Sneaks away quietly: “I avoid them…”

- Panel 4: A giant book monster named Finals: “…but exams like me!”

Output:

Challenges in Building Comic War

No project is without hurdles. Here are some I faced:

- Vague Inputs: Users tend to give short ideas. Without enhancement, outputs look bland or vague due to limited information. Solution: strict screenplay expansion.

- Image Failures: Sometimes image generation stalls. Solution: automatic fallback to a backup service.

- Cropping Issues: Speech bubbles got cut off. Solution: explicit composition rules in prompts.

- Copyright Risks: Some clips reference famous movies. Solution: auto-removal of movie names/brands in the screenplay.

Beyond Comic War

Comic War is just one use case. The same engine can power:

- Meme Generators: Auto-generate viral memes from trending clips.

- Educational Comics: Turn boring lectures into 4-panel explainers.

- Marketing Tools: Generate branded storyboards for campaigns.

- Interactive Storytelling: Let users guide stories panel by panel.

In short, anything that combines humor, visuals, and personalization could benefit from this approach.

My DHS Experience

Comic War started as one of our proposals during DHS, and it is something very personal to me. I worked with my colleagues, Mounish and Badri, and we spent hours thinking together, tossing ideas and concepts out there, rejecting ideas, and laughing at things we came up with, until we finally found an idea we thought we could really do anything with: “How about we take a short video and make a comic strip?”

We submitted our idea, incognizant of what would happen… and we were surprised when it got selected. Ultimately, we had to create it, each piece by piece. It entailed many long nights, lots of debugging, and plenty of excitement every time something ‘worked’ the way we wanted it to. Seeing our idea move from just an idea to something real was honestly one of the best feelings ever.

Response from Folks

What we witnessed, when we let it loose, was well worth it, as all the responses were positive. People kept telling me it was great, and that they were intrigued by the idea and the process of how we arrived at the idea and then made it happen.

Perhaps the most surprising part for me was how people began to use it in ways I never considered. Parents began to make comics for their children, literally turning mundane little stories into something special and visual. Others started exploring and experimenting, thinking of the most amazing prompts and then seeing what happened next.

For me, that was the most exciting part, seeing people get excited about something we created and then go and create something even cooler, and to see this little idea moment turn into something like Comic War was amazing.

Conclusion

Building Comic War was a lesson in orchestration, splitting the job between a storyteller and an illustrator.

Instead of hoping a single model “figures everything out,” we gave each part a clear role:

- One expands and structures the idea

- One draws faithfully

The result is something that feels polished, personal, and fun.

And that’s the point: with just a short video and a silly idea, anyone can create a comic that looks like it belongs on the internet’s front page.

Frequently Asked Questions

A. A YouTube Short link (~30–40 sec) and a one-line idea. The system analyzes the clip with Gemini, expands your idea into a 4-panel screenplay, and then the image model draws it.

A. Gemini drafts the 4-panel script. GPT-Image-1 draws it. If OpenAI fails, Imagen is used automatically. This separation keeps results consistent.

A. The screenplay removes brand and character names, avoids likenesses, and keeps a stylized comic look. You supply videos that you have the right to use.